BEAST FABLES IN ANTIQUITY

509

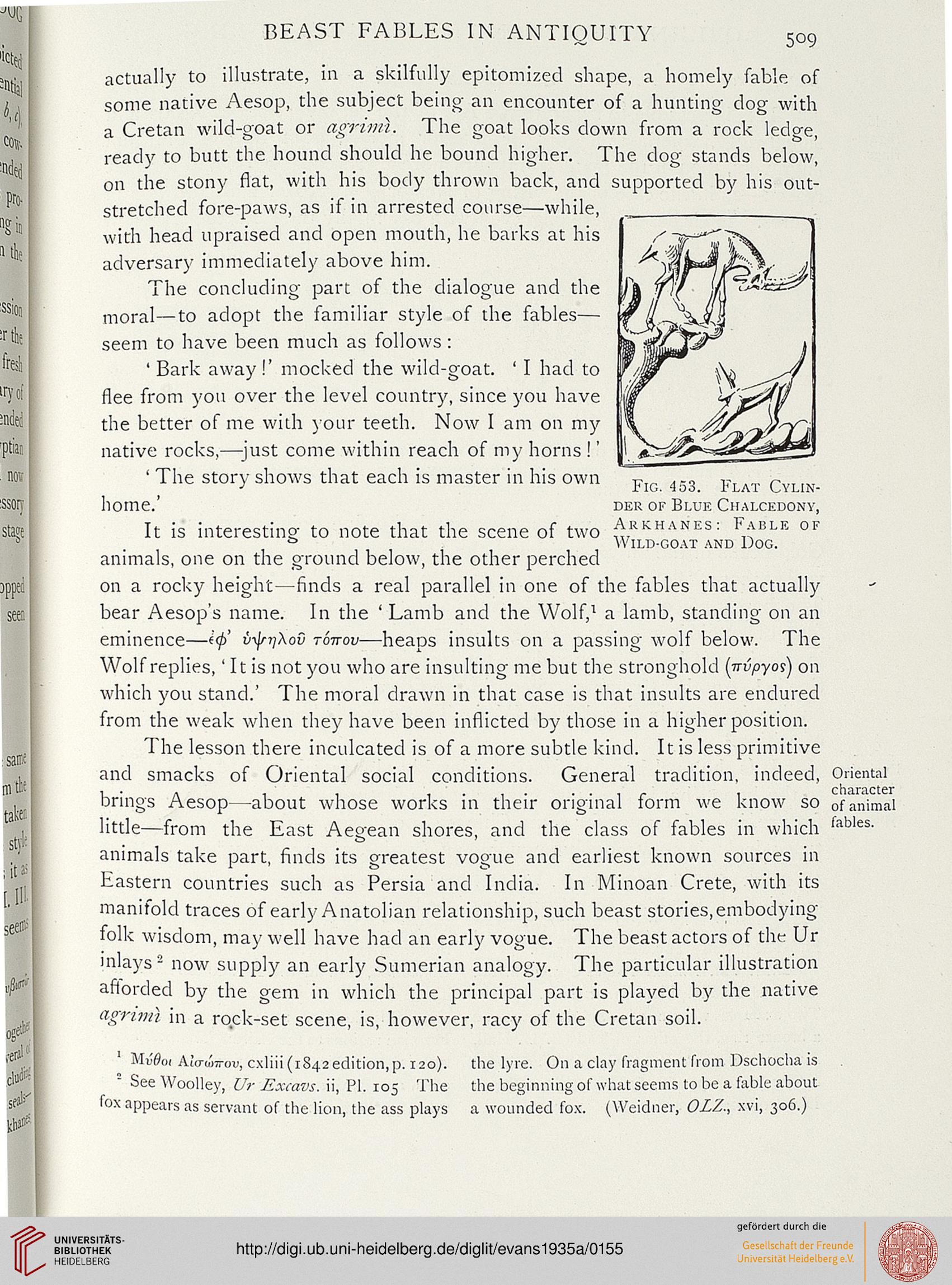

Fig. 453. Flat Cylin-

der of Blue Chalcedony,

Arkhanes: Fable of

Wild-goat and Dog.

actually to illustrate, in a skilfully epitomized shape, a homely fable of

some native Aesop, the subject being an encounter of a hunting dog with

a Cretan wild-goat or agriml. The goat looks clown from a rock ledge,

ready to butt the hound should he bound higher. The dog stands below,

on the stony flat, with his body thrown back, and supported by his out-

stretched fore-paws, as if in arrested course—while,

with head upraised and open mouth, he barks at his

adversary immediately above him.

The concluding part of the dialogue and the

moral—to adopt the familiar style of the fables—

seem to have been much as follows :

' Bark away!' mocked the wild-goat. ' I had to

flee from you over the level country, since you have

the better of me with your teeth. Now I am on my

native rocks,—just come within reach of my horns !'

' The story shows that each is master in his own

home.'

It is interesting to note that the scene of two

animals, one on the ground below, the other perched

on a rocky height—finds a real parallel in one of the fables that actually

bear Aesop's name. In the ' Lamb and the Wolf,1 a lamb, standing on an

eminence—l<j> infnjXov tottov—heaps insults on a passing wolf below. The

Wolf replies,' It is not you who are insulting me but the stronghold (nvpyos) on

which you stand.' The moral drawn in that case is that insults are endured

from the weak when they have been inflicted by those in a higher position.

The lesson there inculcated is of a more subtle kind. It is less primitive

and smacks of Oriental social conditions. General tradition, indeed, Oriental

brings Aesop—about whose works in their original form we know so ofanimal

little—from the East Aegean shores, and the class of fables in which fables-

animals take part, finds its greatest vogue and earliest known sources in

Eastern countries such as Persia and India. In Minoan Crete, with its

manifold traces of early Anatolian relationship, such beast stories,embodying

folk wisdom, may well have had an early vogue. The beast actors of the Ur

inlays2 now supply an early Sumerian analogy. The particular illustration

afiorded by the gem in which the principal part is played by the native

agrinii. in a rock-set scene, is, however, racy of the Cretan soil.

Mu'#(,j Aicrw-ou, cxliii(iS42 edition, p. 120). the lyre. On a clay fragment from Dschocha is

1 SeeWoolley, Ur Excavs. ii, PI. 105 The the beginning of what seems to be a fable about

fox appears as servant of the lion, the ass plays a wounded fox. (Weidner, OLZ., xvi, 306.)

509

Fig. 453. Flat Cylin-

der of Blue Chalcedony,

Arkhanes: Fable of

Wild-goat and Dog.

actually to illustrate, in a skilfully epitomized shape, a homely fable of

some native Aesop, the subject being an encounter of a hunting dog with

a Cretan wild-goat or agriml. The goat looks clown from a rock ledge,

ready to butt the hound should he bound higher. The dog stands below,

on the stony flat, with his body thrown back, and supported by his out-

stretched fore-paws, as if in arrested course—while,

with head upraised and open mouth, he barks at his

adversary immediately above him.

The concluding part of the dialogue and the

moral—to adopt the familiar style of the fables—

seem to have been much as follows :

' Bark away!' mocked the wild-goat. ' I had to

flee from you over the level country, since you have

the better of me with your teeth. Now I am on my

native rocks,—just come within reach of my horns !'

' The story shows that each is master in his own

home.'

It is interesting to note that the scene of two

animals, one on the ground below, the other perched

on a rocky height—finds a real parallel in one of the fables that actually

bear Aesop's name. In the ' Lamb and the Wolf,1 a lamb, standing on an

eminence—l<j> infnjXov tottov—heaps insults on a passing wolf below. The

Wolf replies,' It is not you who are insulting me but the stronghold (nvpyos) on

which you stand.' The moral drawn in that case is that insults are endured

from the weak when they have been inflicted by those in a higher position.

The lesson there inculcated is of a more subtle kind. It is less primitive

and smacks of Oriental social conditions. General tradition, indeed, Oriental

brings Aesop—about whose works in their original form we know so ofanimal

little—from the East Aegean shores, and the class of fables in which fables-

animals take part, finds its greatest vogue and earliest known sources in

Eastern countries such as Persia and India. In Minoan Crete, with its

manifold traces of early Anatolian relationship, such beast stories,embodying

folk wisdom, may well have had an early vogue. The beast actors of the Ur

inlays2 now supply an early Sumerian analogy. The particular illustration

afiorded by the gem in which the principal part is played by the native

agrinii. in a rock-set scene, is, however, racy of the Cretan soil.

Mu'#(,j Aicrw-ou, cxliii(iS42 edition, p. 120). the lyre. On a clay fragment from Dschocha is

1 SeeWoolley, Ur Excavs. ii, PI. 105 The the beginning of what seems to be a fable about

fox appears as servant of the lion, the ass plays a wounded fox. (Weidner, OLZ., xvi, 306.)